The Good Deed and the Power of Fiction

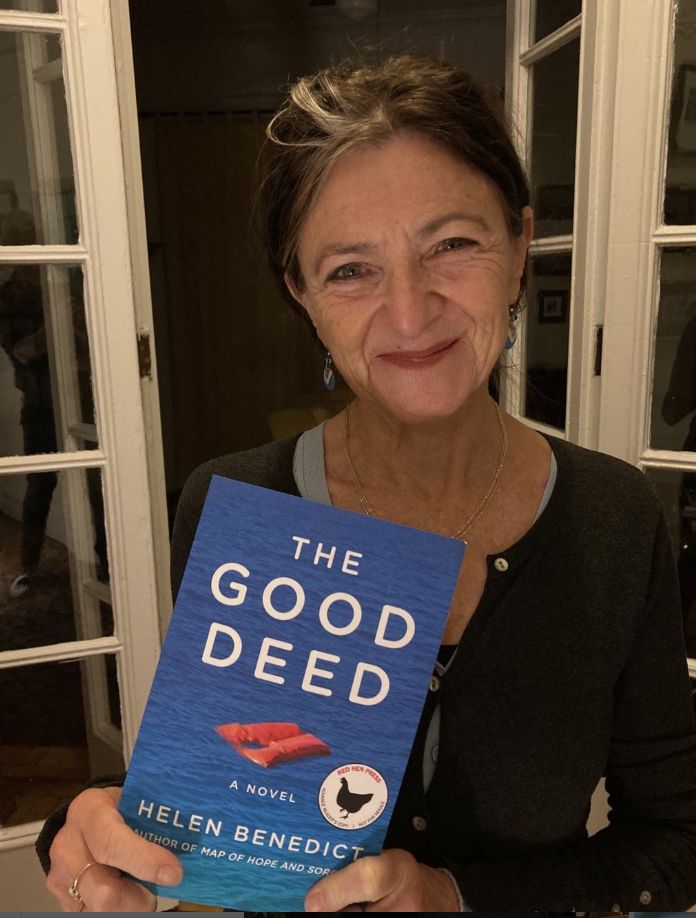

The Good Deed is based on your experiences visiting refugee camps in Greece. How did you balance factual accuracy with fictional storytelling in this novel?

I believe that if one is going to write fiction set in real places and encompassing real events, one should be accurate about those. So although the people in my novel, The Good Deed, are all invented, I like to say they all could exist. Likewise, even as the events that happen to those people are also invented, they, too, could happen to anyone in their circumstances. Thus I used my research in the camps, my talks with real people, and my fact gathering to make the story as plausible and authentic as possible.

What motivated you to transition from nonfiction accounts in Map of Hope and Sorrow to a fictional narrative in The Good Deed?

There are always barriers with real people. One has to worry about putting them in danger, re-traumatizing them, invading their privacy, for a start. But those dangers don’t exist with fictional characters. Thus I feel that I can get deeper into people’s hearts with fiction. I can go deep inside what it feels like to be forced away from your home, what it feels like to live as a stranger in a land that’s hostile to you, what it’s like from moment to moment to live in a refugee camp, and the ways that one can find comfort and sustenance and friendship and love. I wanted to write about the way human beings survive, the hardship, which I find very moving.

And I wanted to do it from the inside, which is the landscape of fiction.

How did your collaboration with Eyad Awwadawnan influence the development of characters and events in The Good Deed?

Eyad taught me so much about life in Syria, life as an Arab, life as a Muslim, life in a refugee camp. He and I combed over every word of my novel together, so he could make sure I made no cultural or other mistakes. He helped steer me away from extremes and stereotypes and he helped me understand my characters from the inside out. And he helped me work within the Arabic language.

Refugees, War, and Gendered Violence

Your work often highlights the unique challenges faced by women refugees. What systemic changes do you believe are necessary to address these issues effectively?

The biggest change to help women is to end mysogyny! Meanwhile, we should all be raising our sons to understand that women are their equals in every way, and not sexual objects there for men’s pleasure or vessels for motherhood alone. We should also be enshrining this fact in the law, ensuring that women have the same rights and opportunites as men have. In refugee camps, single women and survivors of any kind of abuse ought to be given safe and secure housing, medical and psychological care, and a supportive community. Unfortunately, this is not happening. I address more specific systemic changes in the last chapter of my book, Map of Hope and Sorrow.

In your research, what common misconceptions have you encountered about refugees, and how do your writings aim to challenge them?

The world is very busy demonizing refugees these days. Authoritarian, populist and nativist leaders such as Donald Trump in the United States, Viktor Orbán in Hungary and many more like to find scapegoats on which to direct the ire of the populus and distract them from the real threats of climate change, economic injustice and erosion of human rights. This is the oldest playbook in history. Today, people are told that refugees are all lazy opportunists who have come to live off the fat of the land, or are all terrorists, or are religious extemists out to change change our cultures and lifestyles. Or that they are all criminals, murderers and rapists. None of these accusations have any a basis in fact. Research has long shown that immigrants commit fewer crimes than natives and are not interested in changing anybody’s way of life. They simply want to survive and build a decent future for their children. All my books about refugees, fiction and nonfiction, are aimed at counterracting these negative streotypes by reminding readers that refugees are no different from them, and that any of us, with enough bad luck, could be a refugee.

How do you approach the sensitive task of portraying trauma and resilience in your characters without perpetuating stereotypes or causing further harm?

By being specific and accurate. By never eroticising or glamorizing violence or war. By being honest about how destructive violence is, and yet realistic about how people survive. I try very hard never to write the kinds of lies we see everywhere: that war is glamorous, that soldiers are noble, that victims can always rise up and win.

Military Culture and Sexual Violence

Your book The Lonely Soldier brought attention to sexual assault in the military. What progress have you observed since its publication, and what challenges remain?

For a time there was some progress, in that at least the subject of sexual assault was no longer hidden in the military. But now, with Trump in office in the US and his henchman, Pete Hegseth in charge of the military, the department designed to push back against sexual violence has been dismantled, the honoring and recognition of women has been banned, and a culture of white, Christian, macho mysogyny has been glorified. This is a disaster for anyone in the military who has been harassed, bullied or sexually assaulted, and for any woman hoping to be treated with respect.

How did your investigative work on military sexual assault influence your subsequent novels, such as Sand Queen and Wolf Season?

I could never have written either of those novels without the inside knowledge I gained from my three years of interviewing women in the military, and all I read and heard about that very insular and secretive culture. Because of that research, I had the confidence to portray war trauma, sexual assault, sexism within the military, and how all that affects people when they come home from war.

What ethical considerations guide you when writing about real individuals’ experiences with trauma and violence?

I start by making sure I understand the risks they face. Are they living without legal protection? Are they under threat? Are they still too shaken to speak about certain topics? And how I can protect them on these fronts? It is very important to treat any source who has been traumatized as a partner, not someone to get something out of, so you can discuss how best to protect them together. It’s important to be respectful and sensitive, and not to force anyone to tell you anything they don’t want to. I like to give my sources control over what to say about themselves, and to make sure we understand each other’s goals in doing these interviews in the first place. Why do they want to tell me their stories? And why do I want to tell them myself? Find shared goals so you can work together toward the same end.

Writing Across Genres and Teaching

How do you decide whether a story should be told through fiction or nonfiction? What factors influence this choice?

I don’t decide – it doesn’t work that way. What inspires me to write nonfiction is when I see an injustice that isn’t understood or known enough about, and so feel I need to let the public know. What inspires fiction can be a visual image, a sentence, the sketch of story I heard somewhere once. Novels grow out of characters, nonfiction out of facts.

As a professor at Columbia University, how do you incorporate your fieldwork and research into your teaching methodology?

I bring all I learn out in the world into my teaching. I teach courses on social justice journalism, so all my work on the miltary, war, refugees has been useful. It helps me advise students on ethical interviewing, on research, and on style.

What advice would you offer to aspiring journalists and writers who wish to cover topics related to war, refugees, and social justice?

Do your homework. Read as much as you can about your chosen subject. Don’t go in with a fixed idea you want to prove, go in looking for answers and stories you might not even expect. Prepare to have your eyes opened, your mind changed. Make sure you know why you are pursuing this subject and why your subjects want to talk to you. Treat people with respect. Never make a promise you can’t keep. Never break a promise you have made. Above all, be honest.