Interview Series: Eco-Media Dialogues: Climate, Culture, and Critical Communication

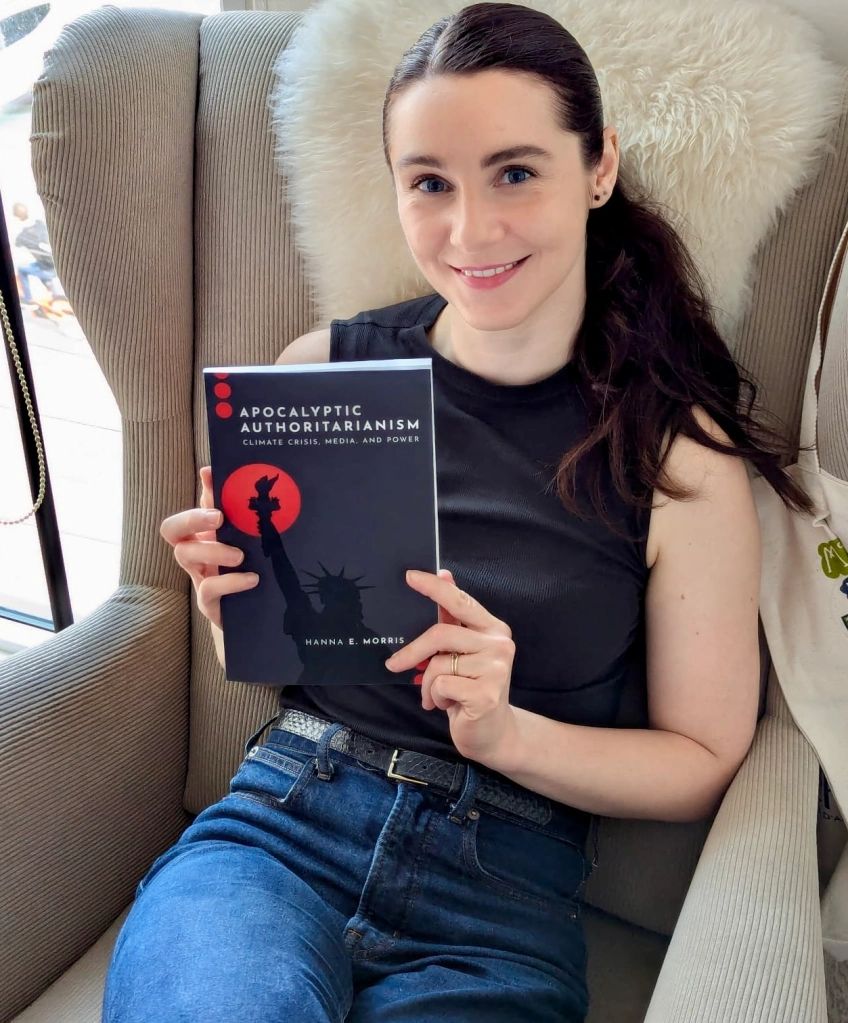

Based on the Book Apocalyptic Authoritarianism

In your book, you introduce the term “apocalyptic authoritarianism.” What led you to develop this concept, and how do you see it shaping media narratives around the climate crisis?

Critical scholars of social change often refer to particularly influential ruptures or events in historical time as “critical junctures” or “hot moments”, within which there is the opportunity to both challenge the status quo and imagine different societal relations and more equitable political structures, as well as the profound risk of falling back onto traditional structures of power and simplified narratives that deepen as opposed to upend existing inequities. The year 2016 in the US—where I am originally from and was living at the time—certainly felt like a very “hot moment” where a lot was in flux, and this heat hasn’t come close to letting up with yet another highly fraught Trump electoral victory in November 2024.

In place of uncovering and combatting Trump’s authoritarian aspirations head-on, however, in this “hot moment” of heightened national anxieties, I found that US news reports and commentaries opted for an apocalyptic rendering that obscured—as opposed to illuminated—what was going on. It became difficult to distinguish one catastrophe from another, let alone remember and keep track of each specific assault on democracy that merged into one indecipherable throng of disarray. And within this reported disarray, simplified narratives came to steer news media coverage. Through these simplified narratives, traditional figures of power were positioned as “visionary sages” that needed to be followed in order to return the US back to its supposed previous steady state. Conversely, young progressives who questioned these traditional figures and who demanded more transformative change were cast as destabilizing forces that needed to be stopped for the sake of the nation.

It’s here where, in my new book, I identified a new mode of reactionary politics that I’ve called “apocalyptic authoritarianism” to describe the reactionary posturing and political alignment of historically privileged figures transcendent of the partisan center and right who are united through a common enemy of the so-called “new” New Left and a shared appeal to apocalyptic visions of “total crisis.” According to this reactionary logic, only “traditional” authorities and “pro-American” saviors can bring back order by eliminating all “unruly” Others leading the nation astray and away from the US’s exceptional and supposedly God-ordained and glorious destiny. In my book, I show how many mainstream news stories and commentaries on climate change—which for the first time was extensively picked up and covered by the US press in the late-2010s—was subsumed within this “total crisis” narrative. In turn, climate journalism in the US began to entrench as opposed to question the reactionary currents of apocalyptic authoritarianism.

Many climate stories in mainstream media carry a nostalgic tone, often idealizing the past. How do you think this framing impacts society’s perception of the crisis? Does it discourage meaningful action?

Yes, notably, at the center of the US climate beat today are nostalgic memories of America’s yesteryears that have been especially brought forward in news stories, images, and commentaries since 2016 to, in part, provide a clearer sense of direction amid the perceived “total crisis” of the present. National myths of grandeur, exceptionalism, and dominion are reactivated and used to orient the news media’s interpretation of unfolding events. Significantly, there is an evident desire for a return to an imagined post-World War II “golden age” in particular—which is a period when many Americans imagine that the US was at its pinnacle of global power.

It is not inconsequential that this romanticized postwar period pre-dates the Civil Rights movement and radical, pro-democracy politics of the late-1960s. This pre-Civil Rights, early postwar era was a period when historically privileged figures were on more solid ground in the US. This privilege is precisely what young social and climate justice activists are again questioning today just like their progressive forbears, and also precisely what traditional centers of power are desperately trying to cling to, protect, and fortify once more. Ultimately, the rampant media fearmongering of climate justice activists across the US national press, concerningly, works in favor of an antidemocratic political project and it is often a deliberate strategy used to delay and obstruct any and all climate action by those with a stake in maintaining the status quo.

You note that climate reporting increasingly relies on “us versus them” framings. How does this affect democratic dialogue? Did you notice a specific shift in this narrative during the Trump era?

In my book, I show how via an “us versus them” media framing, there is a concerning concretization of the boundaries around who should and who should not be included in climate decision-making process and in American politics altogether. Young progressives—and especially young, progressive women of color such as Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez who is a key champion of the Green New Deal— are clearly being Othered and delegitimized as dangerous and militant “Others” who should not be included in climate, party, or national deliberations. There is a growing consensus across the US national press from the center to the right that a “woke” or so-called “new” New Left is a de-stabilizing force that must be stopped.

At the same time as these young, progressive women of color are being represented as threatening to national stability and impeding a return to “normalcy,” many news reports conversely celebrate green tech and market “fixes” developed by older, whiter, and more “moderate” and “reasonable” men as the “right” response to climate change, fully capable of steadying the ship and reorienting the nation back on to its previous course of Manifest Destiny.

This demarcation of right and wrong responses to climate change via the disparagement of young women of color – a historically marginalized group in the US, and glorification of older white men – a historically privileged group in the US, is indicative of wider, patterns in U.S. media and political discourse following Trump’s 2016 election of which I refer to as apocalyptic authoritarianism.

Are issues like class, race, and geography sufficiently addressed in climate reporting today? What role can alternative or community-based media play in making these dimensions more visible?

My book shows how in the age of Trump, the most prominent news publications of record in the US are not sufficiently reckoning with issues of class, race, gender, and justice. And with the increasingly privatized enclosure of social media spaces, such as Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter, coupled with the increased physical policing of progressive movements and gatherings on the ground, there are fewer and fewer alternative forums where these mainstream narratives can be countered and contested.

Climate journalism does not need to be like this. It can move beyond a nostalgic longing for an imagined national past and overt celebration of traditional figures of power. But despite notable efforts by a few climate media initiatives such as Covering Climate Now’s recently launched “89% Project”—which urges journalists to report on the 89% of people in the world who want strong, government-led climate policy programs like the Green New Deal, most major news publications still continue to cover the “climate story” with wary caution directed at protest movements and grassroots politics. A reimagined climate journalism capable of contending with and combatting apocalyptic authoritarianism must engage with as opposed to fear and fearmonger about radically democratic politics. This is an entirely possible as well as incredibly needed task that many community-based and local climate media outlets are already doing despite the many financial and political obstacles they face.

Media, Culture, and Activism

How should global media approach the climate crisis? Is it possible to reshape the language of news reporting? What does a critical climate communication framework offer as an alternative?

In the conclusion of my book, I detail some tangible proposals for how to begin this re-imaginative work. One thing is clear: apocalyptic authoritarians gain their legitimacy through the construction of a so-called “woke” and “extreme” contingent of leftist “radicals” who are blamed for present-day chaos. Fearmongering and dualisms of “us versus them” are used to legitimize antidemocratic dynamics of power and must be broken. A reimagined climate journalism capable of contending with and combatting apocalyptic authoritarianism, therefore, must center many different subjectivities, knowledges, and experiences in stories on climate change.

What role do artists, designers, and activists play in the visual narrative of the climate crisis? Can visual culture shift the way people engage with ecological issues?

A visual culture that moves away from apocalyptic renderings is crucial. Artists and activists can create more deeply contextualized images and can show how there are many possible responses to climate change proposed by lots of different people from diverse places. Different ways of visually representing climate change beyond an apocalypse can poke holes in the fantasies of would-be apocalyptic authoritarians. It’s here where the myth of a “silver-bullet” technological or green capitalist “fix” can be countered by alternative media and open more radically democratic pathways.

You work across media studies and environmental studies. What are the strengths and challenges of this interdisciplinary approach when thinking about the climate crisis?

An interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approach that integrates and learns from different knowledges and experiences is essential. While it’s challenging to do this kind of work, all climate scholarship should be interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary, I think!

What potential does digital media hold in the struggle for climate justice? Can alternative digital platforms or local media initiatives help reshape dominant narratives?

Local and digital media that actively reclaim spaces that are currently dominated by authoritarian figures and a wealthy and powerful few are needed now more than ever. It’s so important that we push back against the antidemocratic seizures of public forums for communication. We can and must push back. Many amazing activists and media-makers are already leading the way on this. It’s so crucial to support the work of independent and local media-makers, especially amid this boiling hot moment of antidemocratic and climate threats.