Interview Series: Climate Crisis in Cinema: Rewriting the Planet’s Story Through Visual Narratives

Cinema and the Anthropocene

In Inhospitable World, you explore how cinema functions not only as a medium of representation but also as a site of environmental struggle and aesthetic refusal. How do you think cinema—especially narrative cinema—responds to the epistemological and material challenges of the Anthropocene?

Narrative cinema, as opposed to documentary, responds to the Anthropocene in a few different ways. And, of course, much depends on how the Anthropocene is defined as a political and environmental crises, historical phenomenon, and/ or cultural logic. I’ve been interested in narrative films that thematize anthropogenic weather and pointedly artificial environments, on one hand, and others that bring to the fore, as a matter of design, massive infrastructure projects such as mega-dams, highways, big agriculture (to name a few) that have altered, profoundly and at a planetary level, the surface of the earth and the movement of water, animals, and people. There are contemporary narrative films that respond to the Anthropocene thematically by taking up plots about climate change. But there are others that can be more interesting to study that set fictional stories against backdrops in which the forces of the Anthropocene are on display, but not at the forefront of the story.

And we can also study fiction films made in studios, long before the Anthropocene was discovered, that thematize weather and atmosphere as designed or artificially produced rather than naturally given. Sometimes this is obvious in the plotting or a matter of knowing production history. This idea of artificial or anthropogenic weather, “nature,” and world have always been at the center of narrative films where the need to control and reproduce environmental conditions is paramount to efficient production, perhaps especially when, in the film, the effect is supposed to look contingent and natural. In this way, we can see designed environments (including calamitous weather) as an aesthetic practice of cinema that is connected to the cultural forces and impacts that give rise to Anthropocene conditions.

The term “inhospitability” that you foreground resonates with the unlivable conditions of both planetary ecosystems and cinematic spaces. How does this notion help us understand the aesthetic or ethical function of discomfort in environmental film?

Inhospitality is meant to describe a few things. First, it refers to the world of the Anthropocene that is increasingly unlivable to most Holocene life. I focus on the 20 th century and period of the Great Acceleration in which the explosive rise of consumer capitalism and visions of a “good life” in the mostly white western world destroy the environmental conditions on which all life on the planet are predicated. Cinema is complicit with this culture of accumulation.

Historically Hollywood films have advertised images of “the good life” to spectators all over the world to imitate, and cinema is, for the most part, a resource-intensive entertainment in all phases of production, distribution, and exhibition, whether as celluloid projected in the theater or as streaming content. But this also an artform that sheds light on the climate catastrophe. The world we see projected on screen represents and may mirror the one we inhabit. Thus, cinema offers a way of viewing our world at a remove from which we may contemplate the relationship between a pattern of life and the natural resources or petrochemicals that give rise to it.

Second, hospitality speaks to the ethical relationship between guests and hosts, of who welcomes whom. Inhospitality gestures to a refusal of these terms, and not only between people. Hospitality between people presumes that the earth is a home to the lifeforms that have evolved here. The earth’s hospitality is no longer assured. Finally, I am interested in the world of the film and the image. What does it mean to take up residence in an image? Are there forms of environmentally-minded cinema that refuse that invitation? Other films may welcome us to an image where we may not find a place for living in the world.

How might film’s aesthetic choices—such as composition, sound, duration—contribute to either revealing or concealing ecological fragility?

Cinema is an aesthetic arrangement of material that viewers may not otherwise perceive or take the time to notice in the real world, and this goes for a range of phenomena people, animals, places, and environments. Cinema allows us to take another look and have a second or third thought about the things we see and hear; a film may give us a view on the world that exceeds or defamiliarizes human perception and attention. I am among scholars interested in so-called slow cinema, Tsai Ming-liang, Jia Zhang-ke, Kelly Reichart, to name just three directors with environmental attunements and a penchant for long takes that give us time to become absorbed in an image and its sounds and also to become curious about what is beyond the frame. At the same time, cinema may also keep the world and its crises from view. It all depends on who is conceiving of the film, controlling the camera, and making decisions about what film-goers get to see.

Genres and Forms

There is often a tension between mainstream cinema’s spectacular tendencies and its capacity to provoke ecological awareness. Do you believe that popular genres (sci-fi, disaster, thriller) are capable of engaging critically with the Anthropocene—or does this role fall more effectively to experimental or documentary forms?

Big-budget mainstream films may not take the political risks of documentary and experimental films, and so it makes sense to look beyond the cineplex for meaningful work about our climate crisis. But this is also where film criticism intervenes to consider how even seemingly apolitical or banal genre films are saying something worthy of attention. For example, I find the totally banal Geostorm to be kind of interesting as a post-apocalyptic film. The scenario is that the planet’s entire climate system has collapsed and is now regulated through satellites. When we encounter this post- apocalyptic world, however, it is exactly like the pre-apocalyptic world that brought about the catastrophe in the first place; i.e. the current world. Nothing has changed (not that any character remarks on this fact). And, thus, this silly genre film says something about climate catastrophe, a fantasy of geo-engineering, and a desire to maintain the unsustainable the status quo.

Are there particular films, auteurs, or cinematic practices that you believe manage to narrate environmental precarity without reducing it to cliché or moralism?

There are genres that I think of as having an environmental sensitivity if not sensibility. For example, film noir and its attraction to built environments, bad air, and desiccated urban spaces has deep connections to naturalism and pessimism in ways that show how urban worlds built for human life become unlivable for these characters who rarely survive the film. These are low-budget movies, often shot on location, and feature characters who want but who cannot achieve the “good life” of consumer capitalism that is underwriting the Great Acceleration.

How do genre conventions affect how we conceptualize ecological time, space, and agency?

The film historian and theorist Karl Schoonover is currently writing about auteurs like Max Ophüls and Douglas Sirk in terms of their attention to soot and waste (Ophüls) and the byproducts of petroleum—from plastic to make-up—that are everywhere in the mise- en-scene (Sirk). Another film scholar, Nadine Chan, researches the history of colonial cinema in Malayasia. Chan focuses on the relationship between colonial extraction and the educational films made for colonial subjects whose labor is being extracted along with the colony’s raw materials. Cinema both archives this process and participates in the colonial economy. Finally Brian Jacobson’s recent book The Cinema of Extractions considers how the form of early cinema, especially, is parallel to the raw materials and infrastructures on which cinema relies. If there are many early films about trains, to take just one example, it is because trains carry the materials needed for cinema.

Temporality, Scale, and Representation

The Anthropocene demands that we think across scales—geological, planetary, human. What role can cinema play in making “deep time” and slow violence perceptible to audiences who are accustomed to fast-paced storytelling?

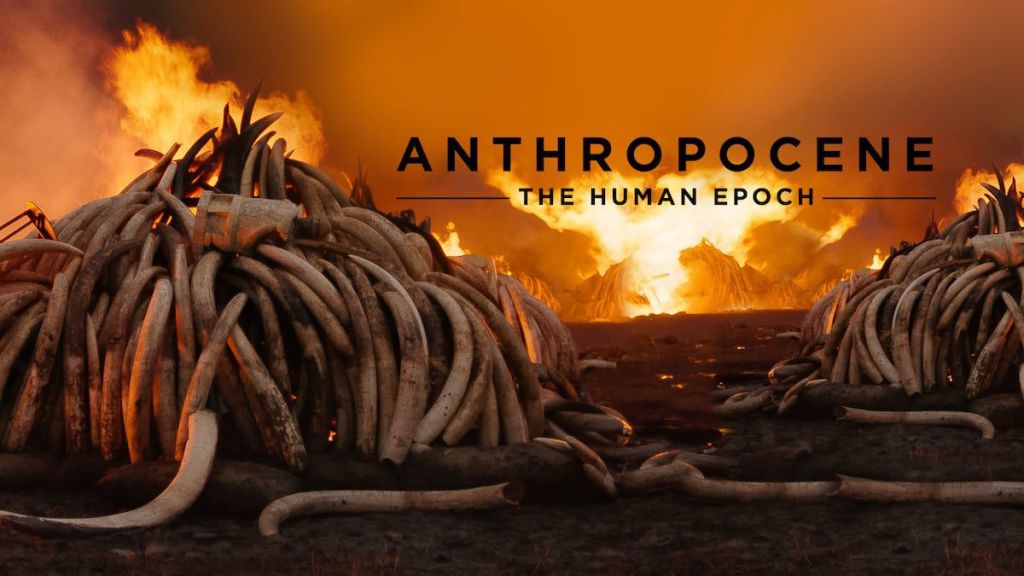

No one film or even group of films alone can tackle a crisis that is so totalizing, planetary, and yet uneven in its signs and stresses. One challenge of representing the Anthropocene is that it is not reducible to a singular event so much as a “step change” in socio-economic activity that accumulates in impact and changes quickly in geological- scale time, but slowly in terms of human perception. Films that have attempted explicitly to illustrate the Anthropocene concept or thesis – such as The Anthropocene: The Human Epoch (2018) or Erde (2019)—can be a bit mystifying to viewers not already familiar with the nomenclature. The visual evidence is not always clear in its illustration. But these films do provide a kind of snapshot of resource extraction and resource depletion, the kinds of human labor and modes of living occurring all over the world that have reshaped the planet and changed its chemistry, with attention to those who suffer most to sustain a way of life in the wealthy global North. The films show us the uneven distribution of wealth and risk, and they move between the scales of satellite images of earth down to the microscopic. The scales of space find a rejoinder in strategies of representing deep time through stratigraphic layers of rock or ice. But the data that geologists use to make the case for a new epoch are not always the most compelling material for films (even if the evidence they produce can be breathtaking). There is also the threat of producing a generalized humanity as opposed to a particularized history of exploitation, racialized capitalism, and the uneven impacts of global warming. As numerous historians and anthropologist tell us, there is nothing inevitable about the way our climate culture has developed, and this is also a danger.

In what ways might film temporality challenge anthropocentric or progress-based narrative structures?

As a geological term, the Anthropocene is also a projection into a deep future. It is a concept that concerns not only the place of human history in the context of Earth’s 4.5 billion-year existence; it is also about the trace that human culture will have left on the planet millions and billions of years from now. The very question should have us consider the long legacy of modern industrial culture. What will be nested in the geological strata to announce that people once roamed this earth? Likely not the meaningful archives of literatures, laws, art, film, and history, but plastics, nuclear materials, and so-called “techno-fossils” discarded by wealthy nations in pursuit of an unsustainable, resource intensive, quality of life and an equally destructive and toxic property of war. A few geologists have proposed that the fallout from nuclear testing has already left a distinct mark all over the planet that could be the most distinct trace of the Anthropocene, since many of the radioactive materials are not “naturally” of this Earth. What is likely to remain in the geological record are not the artifacts we hold dear, but the refuse that capitalist culture discards along with the weapons that destroy us all. In its arresting opening scenes, Wall-E (2008) gives us one version of this future: a planet with abundant trash minus humans and all signs of natural life. How does a robot sort the significance of these remains? This will be the task of alien archeologists who visit our planet the deep future.

What dangers exist in making climate stories overly personal (e.g., through individual heroes or family dramas) or too abstract (e.g., anonymous data, satellite imagery)? Can cinema cultivate a collective emotional register—one that resists neoliberal optimism but still affirms the urgency of ecological care?

There are genres that I think of as having an environmental sensitivity if not sensibility. For example, film noir and its attraction to built environments, bad air, and desiccated urban spaces has deep connections to naturalism and pessimism in ways that show how urban worlds built for human life become unlivable for these characters who rarely survive the film.

What ethical obligations arise when filmmakers attempt to visualize planetary scale processes or speculative environmental futures?

It is a challenge to keep all of these data points in mind and hard not to feel utterly full of despair. So, it is important to find important stories of resistance and scenarios of world repair. We learn that our current state of disastrous ecology is not a natural progression of human life on earth, but a consequence of colonial land-grabs and the capitalist bid to turn the earth and many of its people into raw material and profitable commercial resources.

Darwin’s Nightmare (2004) explores the ecology of Lake Victoria and the disastrous commercial cultivation of invasive species of Nile Perch in its waters. The trade in perch has led to a neo-colonial economy and massive extinction events in the world’s second largest fresh-water lake. Bacurau (2019) turns the table on who or what counts as an invasive species.

Still Life (2006) and This is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (2019) are movies of quiet but powerful protest against state-sponsored mega-dam constructions that force the relocation of everyone in the floodplain and submerge entire cultures under the devastating waters of “development.”

There is no way to completely reverse the course of modern industry and rapacious capitalism, but we may glimpse visions of repair. Honeyland (2019) is one such vision where taking only what you need in moderation is the difference between life and death, not only of bee colonies, but of all life on the planet. If Hollywood once projected an image of the good life based on American style consumer capitalism, cinema can now show us a different way of living, a new version of “the good” in light of our entangled and differently endangered lives.

Narrative Language and Ethics

Do you think cinema must cultivate a new narrative grammar in the Anthropocene—one that goes beyond individual agency or resolution?

Cinema, like the Anthropocene by some accounts, is a product of the industrial revolution. The medium’s radical possibilities with regard to space and time are already attuned to the epochal rupture of the Anthropocene. Indeed, I think cinema is one of the best archives of the Anthropocene because it is so fully implicated in the industrial, cultural, racial, and colonial practices that have laid waste to the planet. It is also a medium that can, as I write above, shows us a vision and version of the world without us.

How might cinematic ethics be redefined to account for nonhuman entanglements, multispecies justice, or posthuman subjectivity?

While much of narrative cinema revolves around people and their psychology, cinema has long been celebrated as an optical medium that, like photography, flattens the ontology between humans, animals, and things, and that may allow us to see a world outside of our ideas and feelings for it. This is a theme in much classical film theory that cinema is a non-human if not post-human artform. By this I do not mean that the cinematic image is neutral. But this possibility for cinema means that it is possible to decenter or even eliminate altogether the human in the frame. There are few films—outside of nature documentaries and experimental films-that do this. But one way to think of film’s role with regard to multi-species justice is to simple look at other creatures, take in their mysteries, their separateness from us, on one hand, and our entanglement with them, on the other.

What risks do filmmakers face when trying to “represent” ecological devastation? Is there a line between visualizing collapse and aestheticizing it?

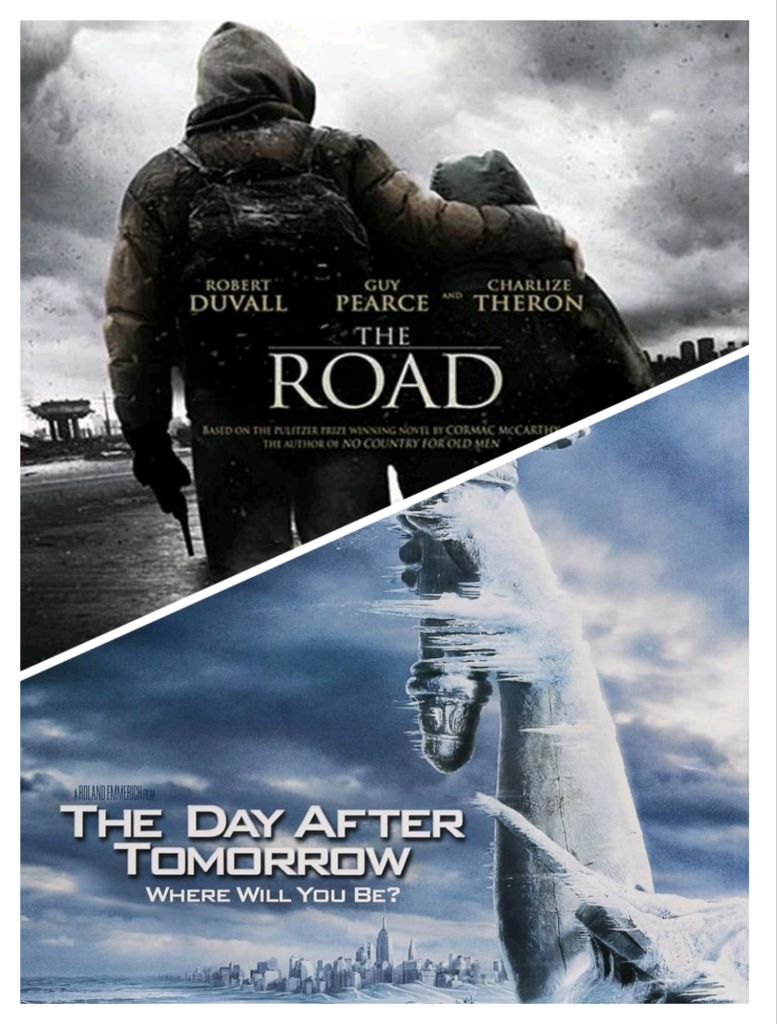

There is a risk in representing climate change that we see in more mainstream climate fiction and eco-disaster movies, such as The Day after Tomorrow (2004, dir. Roland Emmerich), The Road (2009, dir. John Hillcoat), and the Mad Max franchise. These are movies that frighten or distress us with the future loss of a familiar world and homey habitat: a projected future without nature. Rather than push us to reorder the status quo, they threaten with scenarios of its withdrawal. Rather than opening a portal to a new, and hopefully more just world, such dystopic projections want us to want things as they are, to prevent the current world from changing or disappearing. These films make us worry more about the big storm or unnamed event that wipes out the contemporary world. Some eco-disaster movies may even prevent us from seeing that the current state of the world – our giant coastal cities, monocrop agriculture, fossil-fueled mobility – is itself the environmental catastrophe.

Emotions and Audiences

Climate narratives often rely on affect—fear, hope, grief—to mobilize audiences. In your view, what role should emotion play in ecological cinema?

E. Anne Kaplan has written about how climate disaster movies can prompt a form of pre- traumatic stress. These are symptoms viewers suffer not from the violent past, but, proleptically, from the future as it is envisioned on film. In immersive and alarming detail, these eco-disaster movies confront us with a version of a future human subject in motivate viewers to prevent that future ecological collapse, they also keep the emergency in the present from view. As I write above, the petro-cultures and habits of global North consumerism (these are shorthand terms for larger and historically longer phenomena) are the catastrophes.

An alternative to this narrative tendency may be found (to provide just one example) in the films of Tsai Ming-liang, a master auteur for the Anthropocene, and not only because he features inclement weather, failing infrastructure, and epidemiological emergencies in his films (I have written about Tsai’s work in the edited collection What is Film Good For?). Tsai’s queer narrative arcs and long-take slow cinema reveal characters living in a post-apocalyptic world of the present. The catastrophe has arrived, and its effects are already felt, especially by those living on the economic and social margins of Taipei and Kuala Lumpur. Lingering with these people who hardly speak—they convey themselves by the way they walk, gesture, cough, eat—we come to care for them and the conditions that render their world unlivable. Rather that mourn the loss of the world to come, his films may bid us to pause and to consider leaving behind all that was already unwelcoming to these characters, a world we should not want to preserve or carry with us beyond the catastrophes of our current moment.

What dangers exist in making climate stories overly personal (e.g., through individual heroes or family dramas) or too abstract (e.g., anonymous data, satellite imagery)? Can cinema cultivate a collective emotional register—one that resists neoliberal optimism but still affirms the urgency of ecological care?

I think long form documentary, for those with the patience to watch it, can be such a powerful re-set. One film I especially admire is Frederick Wiseman’s Zoo (1993). Today we are in the midst of what several researchers label the Sixth Mass Extinction. Half of the species on Earth are experiencing rapid population declines as a result of human activities, or what one 2023 study in Biological Reviews calls “Anthropocene defaunation.” Zoos and national parks are the few places designated for animal welfare and species management. Wiseman’s observational documentary takes place in the Miami Zoo, celebrated for its new, more natural habitats and limited use of cages. We learn about complex care for animals, the artifice of their surroundings, and the curious ways that wild, domestic, and feral animals are labeled and handled. As an enclosure separated from the rest of the city or the natural world, the zoo resembles a theme park and a film studio. It is as if each species of animal has its own fake backdrop. Wiseman takes us behind the scenes of this institution, which is the last refuge for many species. I find this film deeply sad and, at the same time, so frank about the conditions of animals and humans living in a second nature. It made me curious about scenarios of re-wilding, on one hand, and the ways that nature, animals, and people are partitioned and, in many ways, lonely.